Policemen in riot gear, burnt cars and piles of debris.

Three days after violent clashes between Hindus and Muslims killed six people, parts of the northern Indian state of Haryana remain tense.

In Nuh, where the violence began on Monday afternoon, the streets are empty and shards of glass lie scattered everywhere. Remnants of burnt cars and shops – vandalised and looted by rioting mobs – are chilling reminders of the clashes.

Those killed include two “home guards”, who assist the police in controlling riots and public disturbances. Several policemen were injured.

Authorities imposed a curfew, suspended internet services and deployed thousands of paramilitary personnel after the clashes also spread to Gurugram, a city just outside India’s capital Delhi.

There, a mosque was set on fire and a Muslim cleric was killed in the violence, which continued through Tuesday. Several shops and small restaurants were vandalised or torched.

The state’s government – led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is also in power nationally – has been conducting meetings with leaders of both communities and no major instances of violence have been reported since Tuesday night. Haryana’s Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar has announced financial compensation to the victims and said that the guilty will be punished.

But many locals fear that even a small spark could trigger a fresh wave of violence.

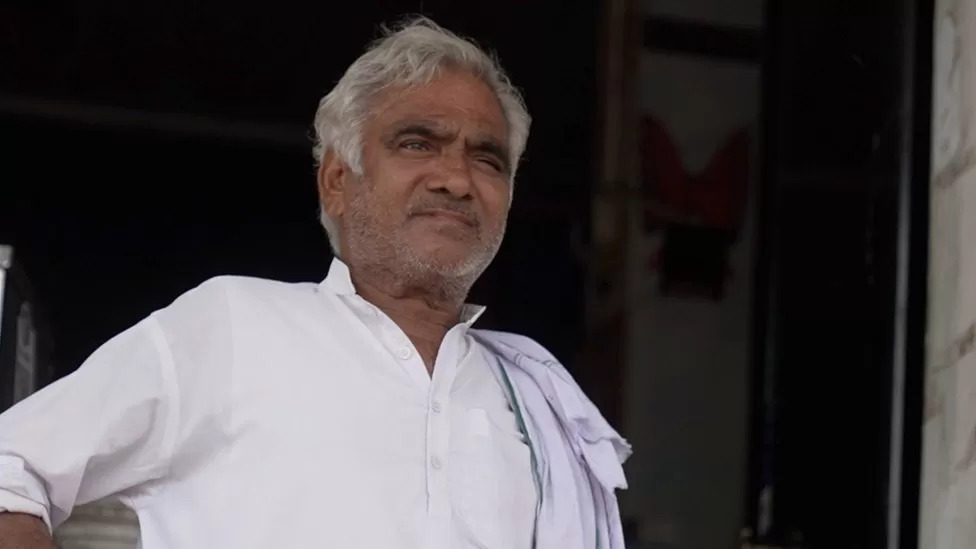

In Nuh, Satyaprakash Garg, 55, sat forlornly outside his sweet shop which he says was looted by a mob of Muslim men on Monday evening.

“I have lost everything,” he says as he gestures at the food strewn across the floor and pieces of shattered glass.

He still shudders when he remembers the fear he felt during the violence.

“I am not angry with those who did this, I am angry at the authorities who allowed this to happen,” he says.

Others sitting with him said that Hindus and Muslims have lived in harmony in Nuh for decades and accused “outsiders” of stoking violence in their city for political gains.

In India, voting on religious lines is common and experts say that communal incidents like these can be politicised in the run-up to elections, which are due in both Haryana and India next year.

The BJP has called the clashes the result of a pre-planned conspiracy. But several opposition parties have accused the party of inaction and said it failed to prevent or stop the violence.

The violence in Nuh began when Hindu and Muslim groups clashed with each other during a religious procession taken out by members of a hardline Hindu organisation.

While details are still emerging, some have alleged that the clash was triggered by a video posted by Monu Manesar – a member of the right-wing Hindu group Bajrang Dal – who is wanted by police in connection with the murder of two Muslim men in February. Mr Manesar, who has been absconding since then, is a well-known cow vigilante in Haryana.

According to reports, he shared a video claiming that he would participate in the procession, which angered local Muslims who have been demanding his arrest.

Misinformation further fuelled tensions. Some reports initially suggested that thousands of Hindu devotees who participated in the procession were stranded in a temple complex, which was surrounded by a violent mob.

However, the head priest later denied this and said that the temple was not harmed during the clashes.

By the time authorities managed to bring the situation in Nuh under control, the news had spread to other parts of Haryana.

Less than 50km (31 miles) away, in Gurugram, a 22-year-old Muslim cleric Saad Ameen was killed and a mosque set on fire.

People who were present say a mob of 150 people broke into the mosque and attacked the cleric and a few others who were inside.

“Kill them, kill them, they kept saying, while shouting religious slogans,” says Sahabuddin, who was sleeping in the mosque at the time of the attack.

He and his friend, Mahmudul Miyan, hid in another part of the mosque and came out only after the mob dispersed. “I could hear gun shots. They broke into the mosque and attacked the imam. Then they poured petrol and set fire to the office,” Mr Miyan alleges.

Riyazuddin – one of the managers of the mosque who had left the premises a few hours before the attack – says he feels lucky to be alive.

“Saad was so young. Why did they have to do this to him?” Mr Riyazuddin breaks down. He says he has been unable to return to the mosque, which is now barricaded and guarded by police.

The mosque, built in 2005, stood in the middle of a busy street with towering residential apartments, and a stone’s throw away from the offices of some of the world’s biggest companies.

Mr Riyazuddin says the structure had always been a source of tension, with some local Hindus opposing its construction. After several legal battles, there was a ruling in favour of it being built, which he says didn’t go down well with some people.

“This was years of bottled-up anger that came out on Monday,” says Riyazuddin. “The rioters used the violence in Nuh as an excuse to burn the mosque down and vent their frustration.”

Source : BBC