“I danced in the dark. I used to light up the room with candles and perform. In the blackout, my naseeb (fate) was going to shine.”

The year was 1962. War had broken out between India and China over a disputed border and the Indian government had declared a state of national emergency.

Fear gripped people as wailing sirens and days-long blackouts became a part of daily life. The future seemed uncertain.

But Rekhabai wouldn’t let the fear of dying dictate her destiny. Instead of shutting shop like the other courtesans (women entertainers), she would dress up in a beautiful sari night after night and sing and dance for the groups of men who came to watch her in the kotha – a Hindi word for a place where professional female dancers performed for men, or sometimes, even a brothel.

Her life had taught her that hardship was often a gateway to opportunity, or at least, survival. Rekhabai’s tumultuous life is now the subject of a book, The Last Courtesan – Writing My Mother’s Memoir, authored by her son Manish Gaekwad.

“My mother always wanted to tell her story,” Gaekwad says and adds that he felt no shame or embarrassment in narrating it as, having lived with her in the kotha up until his late teens, her life was no secret to him.

“Growing up in a kotha, a child sees a lot more than he should. My mother knew this and didn’t feel the need to hide anything,” says Gaekwad. His book – written from the memories his mother narrated to him – gives the reader a shockingly honest look into the life of an Indian courtesan is the mid-1900s.

Courtesans, also known as tawaifs in popular culture, have been around since 2BC in the Indian subcontinent, says Madhur Gupta, an Odissi dancer and author of Courting Hindustan: The Consuming Passions of Iconic Women Performers of India.

“They were women entertainers whose function was to entertain and pleasure royalty and the Gods,” says Mr Gupta. Before India came under British rule, courtesans were viewed as respected performers; they were highly trained in the arts, wealthy and enjoyed the patronage of some of the most powerful men of their times.

“But they also faced exploitation at the hands of men and society,” Mr Gupta says. India’s courtesan culture began to decline after the British – who saw them as “nautch girls” (dance girls) or merely sex workers – enacted laws aimed at curbing the practice.

Their status declined further after India gained independence in 1947 and many courtesans were forced to turn to prostitution to survive. The practice has completely died out now, but stories of famous courtesans and their fascinating lives live on in books and films.

And one such story is that of Rekhabai.

She was born in a poor family in the western city of Pune as the sixth among 10 siblings. Rekhabai doesn’t remember the exact year or date, her memory about time is hazy. Tired of siring five girls, her drunk father allegedly tried to drown her in a pond after she was born.

At the age of nine or 10, she was married off to settle a family debt, and was later sold by her in-laws to a kotha in Bowbazar area in the eastern city of Kolkata.

She was not yet a teenager when she began training as a tawaif, learning to sing and dance. But her life and earnings were controlled by a female relative who was also a courtesan there.

During the India-China war, the relative left and Rekhabai got a chance to take charge of her own life. Her candlelight performances helped her become independent and left her with the realisation that she could be her own provider and protector if she was brave enough.

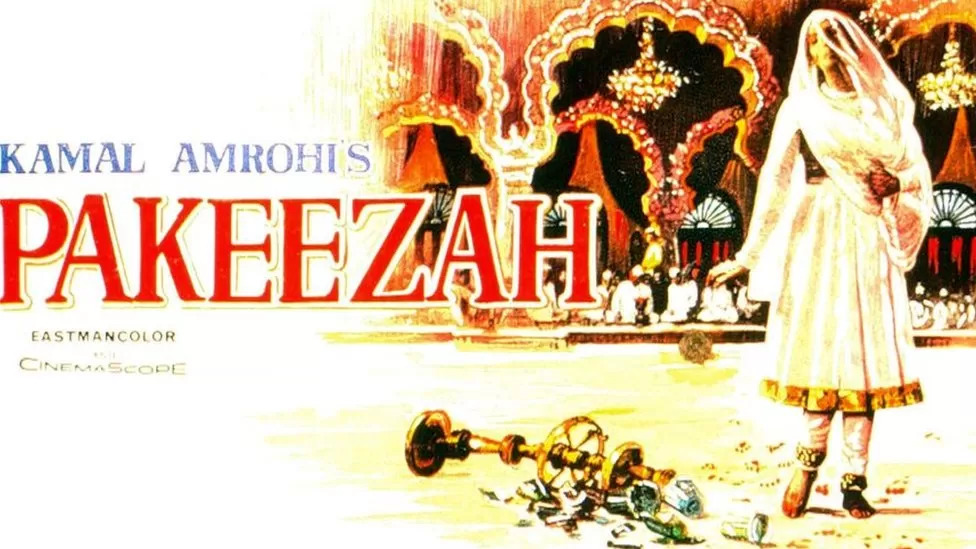

This would become her guiding principle for the rest of her life. Rekhabai – unlike her famous Bollywood counterparts in the films Umrao Jaan and Pakeezah – never pined after a man. She chose not to remarry, despite having a long list of patrons who courted her – from small-time criminals to rich sheikhs and renowned musicians – as it would mean having to give up her life as a tawaif and leave the kotha.

The kotha – the small space in which she performed, lived, raised her child and sheltered various members of her family at different times – ironically became a symbol of freedom and power for her.

Yet, it was also a space fraught with conflict and hardship, where circumstance ate away at innocence, stripped away humanity and evoked destructive emotions like rage, fear and despair.

In the book, Gaekwad narrates some deeply distressing memories his mother recounts, like when a thug pulled out a gun to shoot her after she refused to marry him.

In another place, Rekhabai recounts the abuse she faced from courtesans who were jealous of her success. Some tried to intimidate her by hiring gangsters to lurk outside her room; others called her a prostitute when she wasn’t one.

But the kotha also forged her into the steely woman she became eventually. It’s where she discovered her talent as a dancer, and the power it wielded over men looking to escape their own insecurities or the tedium and melancholia of life.

It’s where she learnt to read men by the way they treated her and to placate egos when needed, or shred them to bits if they threatened to destroy her own.

“I had mastered the language of the kotha. I had to speak it if required,” she says.

But along with this feisty, charming, street-smart performer, the kotha also saw Rekhabai transform into a doting, fiercely-protective mother who did everything in her power to give her son a better life.

As a baby, she kept him close to her in the kotha. She recalls how she would run to check up on him between performances if she thought she heard him cry.

Later, she sent him to a boarding school and then bought an apartment so that he could invite his friends over without feeling embarrassed.

She took pride in the man her son was growing into – even though his English medium-education and more refined upbringing in the boarding school made him different from her in many ways.

In a heart-warming anecdote, she recalls a time her son, who was visiting during vacations, asks for a fork and spoon to eat with.

“I knew of forks [kaanta in Hindi], but I had never heard what it was called in English before… I had to go to the market to buy them when you explained [what it was],” she says in the book.

In the late 2000s, the courtesan culture had completely vanished and Rekhabai left the kotha to live in her apartment in Kolkata. She died in the western city of Mumbai in February. Gaekwad says he will always remain in awe of his mother, her fortitude, talent and zest for life.

“I hope men read this book,” he says, and adds that Indian men have these “constructs around the mother figure, where she has to be a paragon of purity”.

“But I hope this book helps people identify the individuality of their mothers and accept who they are as people, independent from their relationship with us.”

Source : BBC