A recent announcement that the next edition of the Miss World pageant would be held in India has revived memories of its last visit to the country – which involved violent protests, threats of self-immolation and predictions of a cultural apocalypse. The BBC’s Zoya Mateen revisits that tumultuous time, and examines what has changed since then.

The year was 1996. India had moved away from protectionist policies a few years ago, opening its markets to the world. International brands such as Revlon, L’Oreal and KFC were setting up shop in the country, sometimes sparking tensions with local activists and manufacturers.

Beauty pageants were already popular in India by then – two years ago, Sushmita Sen and Aishwarya Rai had become Miss Universe and Miss World, respectively, and would go on to become Bollywood stars. Millions of young women aspired to follow them and embark on glittering careers, though others criticised the emphasis these competitions placed on physical beauty.

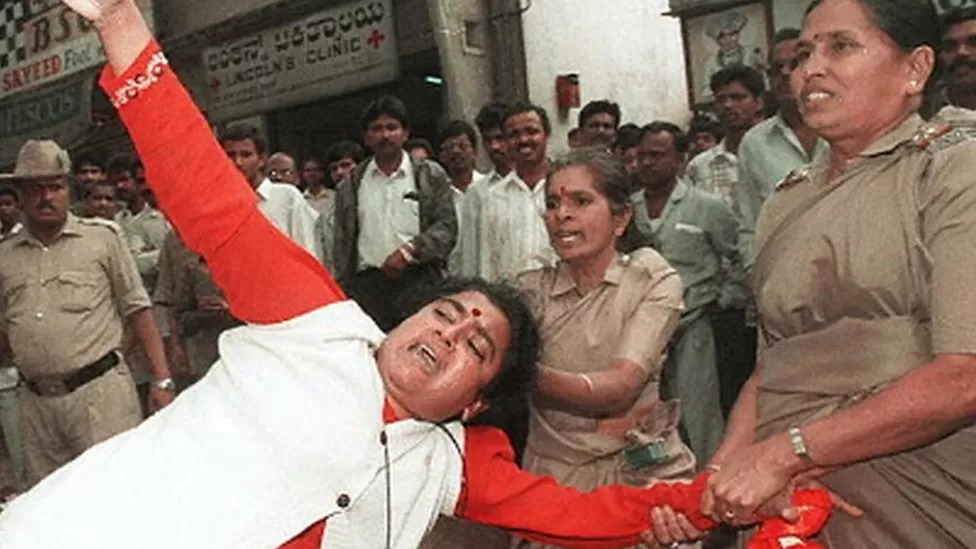

But weeks before the event, violent protests broke out – the objectors ranged from militant farmers to feminists to right-wing politicians – and made global headlines. The swimsuit round had to be moved to Seychelles for fear of the contestants’ safety.

“Defenders of the pageant – and they enjoy the sympathy of most Indians – find it hard to believe that an event so trivial has provoked such a tumult,” the Los Angeles Times wrote.

Filmmaker Paromita Vohra says that the reactions pointed to a tussle between conservative beliefs and the allure of a modern, glitzy world.

“Miss World came to India at the same time as the globalised market. It churned the culture and there was reaction to that churn,” she says.

To be sure, things have changed in India since 1996. The country has won at least half-a-dozen more international pageants and is home to a million-dollar fashion industry which is globally recognised for its imaginative work and detailed craftsmanship. Films and web shows routinely deal with risqué topics; and conversations around women’s clothes and beauty standards have become more nuanced.

The 1996 pageant was organised in India by a company owned by Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan. According to reports, the firm hired more than 2,000 technicians, 500 dancers and even 16 elephants for the event.

But weeks before the show, violent protests broke out in Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore) city, the venue.

Members of a women’s organisation threatened mass suicide, saying that competitions like Miss World would “increase promiscuity and prostitution”.

“Wearing miniskirts is not part of our traditional culture,” a leader of the group told The Washington Post. One man died by suicide “in protest”, CNN reported.

The pageant was also opposed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – which now governs India – as well as a farmers’ group which threatened to burn down the cricket stadium where the pageant would be held (it wasn’t carried out).

Many feminists also protested, with one group holding a mock pageant where contestants were given titles like Miss Poverty and Miss Homeless.

Thousands of police personnel, including several in battle gear, were deployed across the city. Some preliminary events were held on the outskirts of Bengaluru, including an air force base. And of course, the most controversial round was moved out of the country.

Former model Rani Jeyaraj, who represented India at the 1996 pageant, says she was relieved when that happened. “By then, I was already overwhelmed giving interviews to channels. It felt wonderful to be whisked away to a little island where I wouldn’t be harassed all the time.”

The contestants were sheltered from the controversy as much as possible – they were cooped up inside a luxurious five-star hotel for weeks with little outside contact. “But it felt weird to be isolated and not being able to meet friends and family,” Ms Jeyaraj says.

“There was one moment, hours before the final competition, when I almost quit because I was so tired of everything.”

This wasn’t the first or last backlash against beauty pageants and women in swimsuits.

In 1968, a feminist collective organised an event outside the Miss America pageant, where protestors filled a trash can with beauty products. Two years later, activists entered the Royal Albert Hall in the UK and threw flour and rotten vegetables at the Miss World stage in support of women’s liberation.

In 2013, the final of Miss World was shifted from Indonesia’s capital Jakarta to tourist haven Bali after weeks of protests from conservative Islamic groups – there too, the bikini round was scrapped, with contestants wearing “modest, traditional Balinese sarongs”.

In 1996, swimsuits weren’t entirely alien to India – Ms Vohra points out that some Bollywood heroines were already challenging stereotypes and wearing them by then, though it wasn’t common. Several Indian contestants, including Rai and Sen, had also participated in swimsuit rounds at pageants abroad.

But Ms Vohra says that perhaps the anxiety around the 1996 competition was also due to fears that “middle class, upper-caste women” – who usually participated in these events – would be seen wearing swimsuits in public.

But almost three decades after the protests in India, are beauty pageants still as relevant?

There was a time when they allowed women an entry point into a glamorous, economically promising world – if you became a model, you could travel the world, become an icon. Even firebrand American feminist Gloria Steinem participated in one as a teen because she said it seemed “like a way out of a not too great life in a pretty poor neighbourhood”.

In India, pageants have also been a way to enter Bollywood (though the success rate there has been mixed) and “that connection is the reason the glamour around it doesn’t reduce”, Ms Jeyaraj says.

But many young Indian women no longer see a beauty pageant as the only way to do that or consider it an empowering vehicle to achieve their dreams.

Ms Vohra says beauty pageants were never meant to be purveyors of authentic beauty or an ideal standard. Instead, she calls them an economic phenomenon “rooted in the market”.

When Miss World became popular in India, it also brought a different idea of beauty – of tiny sculpted waists, sherbet gowns and a heavily contoured face.

“For instance, women in Bollywood films 30 years ago were more voluptuous than that globalised supermodel standard of beauty,” Ms Vohra says.

But international pageants helped create a new idea of an aspirational female figure.

“And it allowed women to enter that public life only if they were like that,” Ms Vohra says, adding that Indian women today are not dependent on these competitions for opportunities.

“That’s why I think the next Miss World in India will be an event like other events. Perhaps a quaint throwback at best,” she says.

For pageant enthusiasts, though, it is still a world they deeply love and believe in, not some relic of the past.

“These competitions are not just about showing off beauty but also their intelligence and accomplishments at a global platform. It’s their passport to the world,” says fashion designer Prasad Bidapa, one of the judges at the 1996 pageant.

According to him, it is impossible to wish away the allure of beauty pageants because in the end, “everyone wants to look better and dream big”.

“Some people are talented in science, they become scientists. Some people are beautiful, they become superstars.”

Souce : BBC