When such murders are headlined with the term ‘live-in’, the choice of the victim to cohabitate with a partner takes precedence over the criminal act of the offender

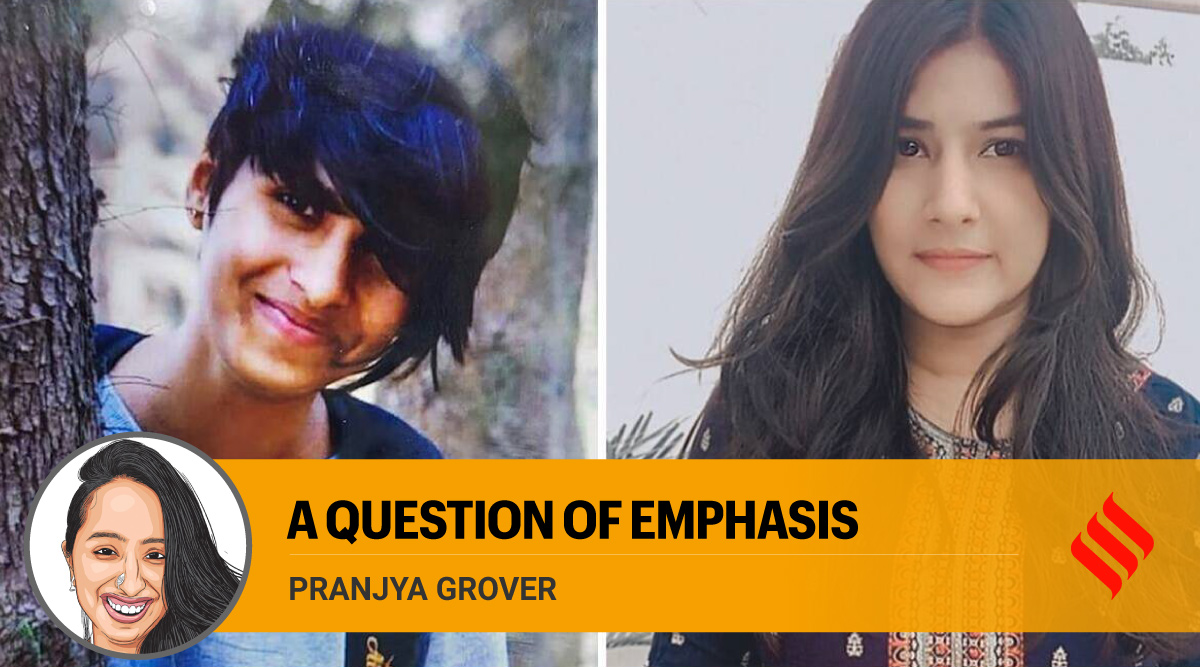

Is there a common denominator between the Shraddha Walkar, Megha Torvi and Nikki Yadav murders? Perhaps the first thing that comes to mind is that they were all in “live-in” relationships with their assailants. Why is that the most prominent detail when these three names are invoked together?

What these cases have in common, in fact, is enraged men. When such murders are reported with headlines that underline the term “live-in” (‘’Man kills live-in partner, hides body in box before calling scrap dealer, IE, February 16), the choice of the victim to cohabitate with a partner takes precedence over the criminal act of the offender. Inadvertently, then, a slew of questions are raised on the moral integrity of the woman.

Like most things, crimes too occur within a context. In a country like India, using the term “live-in” has connotations beyond just being a descriptor for a crime. Cohabitation without marriage is culturally frowned upon. It is also understood as a “western” concept that has seen a recent uptick in the country. Against this backdrop, the term “live-in” strengthens the incorrect perception that people in these relationships are uniquely/more frequently exposed to intimate partner violence. Domestic violence exists outside of cohabiting unmarried couples as well — ranging from parental abuse to marital rape. Thus, lending unnecessary editorial emphasis to a detail that is secondary furthers stigma and often distracts from the issue at hand.

The purpose of a report is to present an objective picture of the incident. A report, by definition, does not purport to insinuate moral judgments on the people in question. Hence, steering clear of such details in the headline and framing the report in a neutral tone is crucial.

One of the primary questions one must ask is: What is the real risk? The live-in relationship or the unsafe partner irrespective of their living situation? Live-in relationships instigate the idea of premarital sex. This automatically creates preconceived notions, especially for the conservative readership in India. It also privileges a particular kind of relationship – a heterosexual, married couple – over other kinds of relationships.

Importantly, this misattribution of risk to co-habitation rather than to abusive relationships simply displaces the more important issue. The purpose should be to encourage conversations towards creating healthy relationships. Additionally, it could create and further narratives that are apathetic to the victim’s plight and could paint them as party to their fate – as though living with someone without being married in itself invites a greater risk of physical or mental abuse.

“Persuasive journalism” refers to the way news items influence their audience’s perception of a certain topic by the way they are written. By repetitively and prominently headlining that the couple was in a live-in relationship, the audience gathers more evidence against that “way” of relationships. This could lead to polarising and negative attitudes and could create more opportunities for families to restrain their children (daughters, most often) from having any agency and/or freedom in their lives. The damage that this does to the victim aside, its impact on the mobility of women across the country and the overall discourse on addressing abuse in India is massive.

It is important to state all the facts clearly. However, repetition of one fact over the others (in Walkar’s case, the offender’s religious identity) subliminally provokes negative attitudes towards the less important details of a crime. Making space for more sensitive reporting such as avoiding disparaging the memory of the victim’s or their family’s image may well be a wiser editorial decision.

Source: india express