As Arnold Dix says, this ranks as the “toughest” tunnel rescue operation he’s ever encountered.

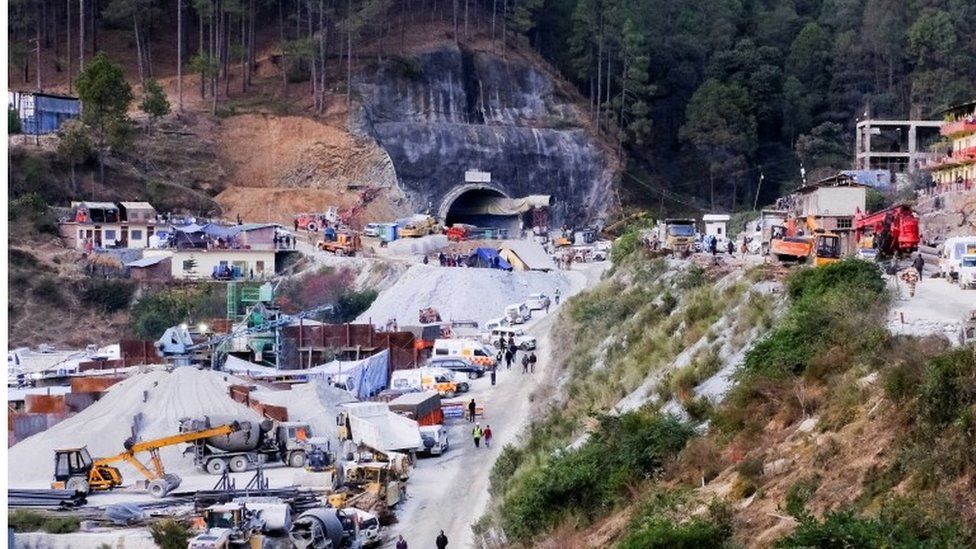

Mr Dix, an Australian underground expert summoned as a consultant by the Indian government, has been spending days and nights outside an under-construction road tunnel in Uttarakhand, where 41 workers have been trapped for more than a fortnight now.

The Silkyara tunnel is part of a $1.5bn (£1.19bn), 890km-long flagship Char Dham project connecting key Hindu pilgrim sites through two-lane paved roads in the Himalayan state. Efforts to clear the 60m blockage and create an exit passage for trapped workers using crawl-out pipes, have faced numerous roadblocks, including the breakdown of the main drilling machine.

“I think this is the toughest [operation] not purely for technical reasons. This is tough because the stakes are very high. No one has been injured and we have to make sure every person inside comes out fine,” Mr Dix told me.

Things can get tricky, Mr Dix reckons. Even what looks like a straightforward fix of using a vertical drill or pipes to bore into the tunnel from the top has hurdles. Instability is a concern in a young and changing mountain topography. There’s a gamble with potential water sources above the tunnel – messing with them could leading to flooding, putting both rescuers and the trapped men at risk.

Bernard Gruppe, a German-Austrian engineering consultancy hired by the Indian company building the tunnel, had said in August that since “the start of tunnel driving, the geological conditions have proved to be more challenging than predicted in the tender document”. It is not clear why an “escape passage” approved for the tunnel in 2018 had not been built until the time when the tunnel collapsed.

To grasp the magnitude of the crisis, it’s important to understand its location – the Himalayas.

The Himalayas are the world’s youngest mountain range, home to the highest peaks, formed some 45 million years ago as a result of the collision and folding of two continental plates. The upward climb of the Himalayas comes with seismic activity – in other words, it’s an earthquake-prone region.

Geologists say many of the rocks in the northern Himalayas where Uttarakhand is located are sedimentary rocks – phyllite, shale, limestone, quartzite – which form when loose sediments of the Earth’s surface become compressed and bond together.

“The problem in this region is that you have varied types of rocks with different strength. Some are really soft, some are more hardened. The soft rocks crumble. This makes the region inherently unstable,” CP Rajendran, a well-known geologist, told me.

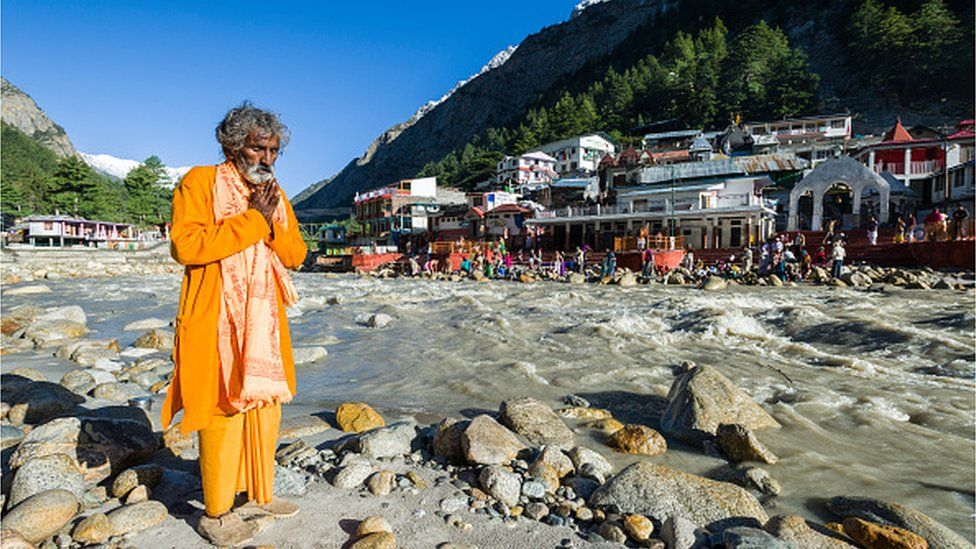

To make sense of this, understanding the wider significance of the region hosting the Char Dham project, spanning four districts of Uttarakhand, is essential.

This region, the birthplace of the Ganges and its major tributaries, sustains over 600 million Indians with water and food. The landscape is dotted with forests, glaciers, and water springs. Crucially, India’s climate is influenced by this area, as its topsoil serves as a significant carbon sink – naturally absorbing and storing carbon dioxide to mitigate the impact of greenhouse gas emissions.

It is here the Char Dham highway project plans to widen the existing highways to double-lane paved shoulder ones with some 16 bypasses, realignments and tunnels, 15 flyovers and more than 100 small bridges.

There are two main road tunnels in the project: the Silkyara tunnel and a shorter 400 metre tunnel in Chamba. Apart from that, there are tunnels being bored for railways and hydropower, including a dozen over 110km (68 miles) for a 125km railway link. Then there are tunnels for a number of hydropower projects – there are 33 such state-run hydro projects in operation, and another 14 being built, according to official documents.

“There has been an intensification of tunnel work in the last 15-20 years”, Hemant Dhyani, an environmentalist, told me. “These mountains are not built for such massive building of infrastructure.”

According to official data, more than 1,000 landslides have hit Uttarakhand, killing more than 48 people so far this year – much of it has been attributed to excessive monsoon rains. Earlier this year cracks developed in hundreds of homes and many streets in Joshimath, a small town in the state. Research indicates that the topsoil in the Himalayas is eroding at three times the national average, leading to the depletion of the region’s carbon sink. In 2013, the town of Kedarnath was hit by devastating floods – triggered by heavy monsoon rains – in which thousands of people were swept away.

Mr Dhyani, a former member of the Supreme Court-appointed expert committee, says the committee’s suggestion to construct a narrower tunnel was disregarded, resulting in heightened blasting activities and an elevated risk of collapse. He believes environmental risk assessments were neglected, as tunnels were exempted due to the project’s segmentation into sections of less than 100km each.

There are contrasting views as well. Manoj Garnayak, an underground construction expert, told a newspaper that that tunnels, if properly executed, do not harm the mountain or hill ecology. He told the Indian Express that tunnel-building technology, dating back about 200 years, is not inherently hazardous – and proper execution involves thorough investigation of the rock intended for tunnel construction, assessing its fragility and solidity.

Environmentalists, such as Mr Dhyani, advocate for a “terrain-specific approach” in all tunnel construction projects, emphasising the unpredictable reactions of geology in different regions. Infrastructure development in the Himalayas should prioritise being “disaster and climate-resilient”. Also, authorities should engage with a broader range of stakeholders to formulate improved policies for environmentally fragile pilgrimage sites, they say.

Authorities now admit that timelines provided for the rescue of 41 men could change due to “technical glitches, the challenging Himalayan terrain, and unforeseen emergencies”. This, for a road, which was designed to offer all-weather connectivity, reducing the sometimes snow-affected stretch from 25.6km to 4.5km and slashing travel time from the current 50 minutes to a mere five minutes.

Ironically, the prolonged wait to rescue the trapped workers building the road is turning out to be a distressing ordeal. “This is a serious wake up call for all of us,” says Mr Dhyani.

Source : BBC