He has been depicted as a fearsome commander, leading a private army of dreadlocked, naked warriors on foot and horseback, armed with cannons to the battlefield.

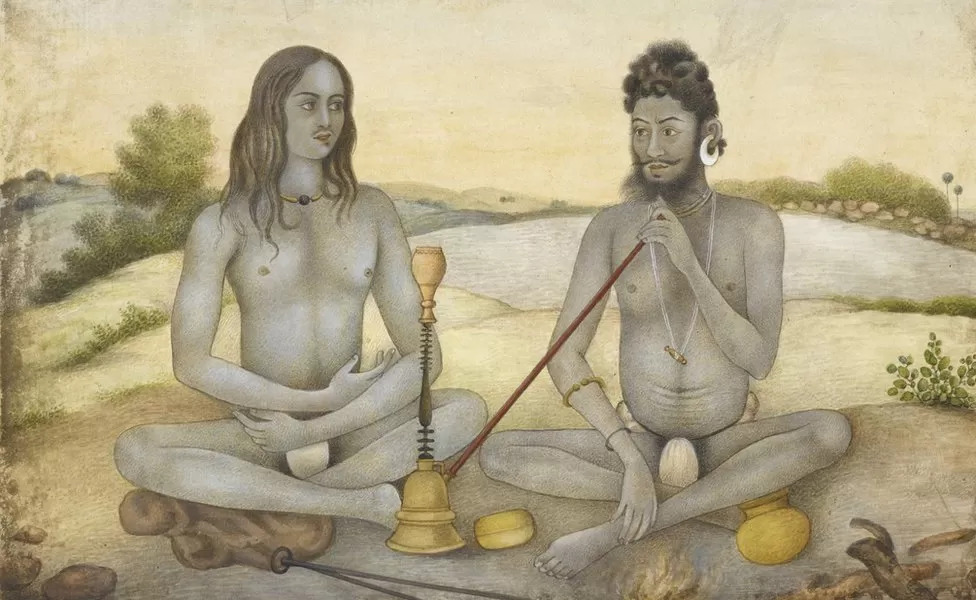

But Anupgiri Gosain was also an ascetic – a man devoted to Hindu god Shiva – or a Naga sadhu, one of the revered holy men of India. These naked, ash-smeared ascetics with matted hair form a prominent sect and are often seen at the Kumbh Mela, the world’s largest religious festival.

Gosain was a “warrior ascetic”, according to William R Pinch, author of Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires. To be sure, the Nagas had a “fearsome and unruly” reputation. The obvious difference is that the 18th Century Nagas were “extremely well-armed and disciplined”, and were said to be “excellent cavalry and infantry troops”, Mr Pinch, a historian at Wesleyan University, Connecticut, told me.

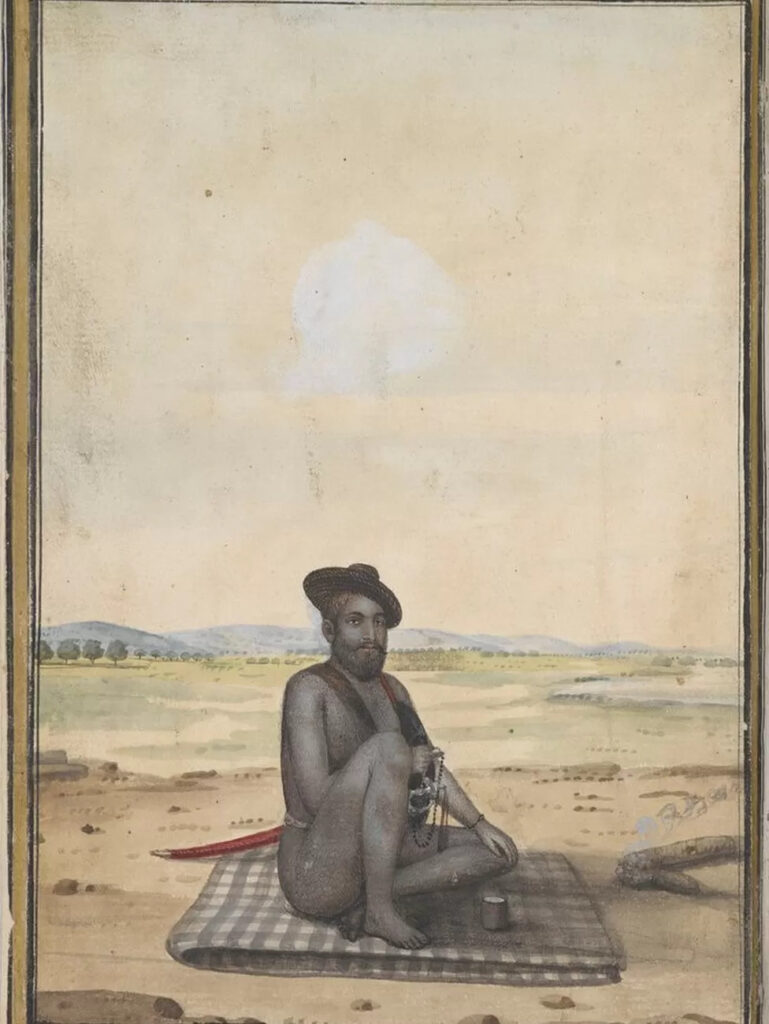

James Skinner, an officer of the East India Company, commissioned a portrait of a Naga soldier in the early 19th century. It portrays a man, barefoot and clothed only in a leather belt that supports his sabre and pouches filled with gunpowder, ammunition, and flint. His hair, thick and matted, is intricately wound around his head resembling a protective helmet. Grasping a long-barrelled musket with his left hand, he displays a vermillion tilak, an emblematic symbol, on his forehead.

“The Nagas had a good reputation as shock troops and in hand-to-hand close-quarter combat. Under Anupgiri, they developed into a full-fledged infantry and cavalry army that could compete with the best,” Mr Pinch said. In the late 1700s, Anupgiri – and his brother Umraogiri – commanded more than 20,000 men. By the late 18th Century, the number of ascetic soldiers, carrying cannon and rockets, increased dramatically.

Author and historian William Dalrymple has described Anupgiri as a “fearsome Naga commander” who was given the Mughal title Himmat Bahadur or ‘Great of Courage’.

In The Anarchy, a history of the East India Company and how it came to to wield dominion over India, Mr Dalrymple writes about the army of Mirza Najaf Khan, a Mughal commander, being joined by a different class of soldiers: the “dreadlocked Nagas of Anupgiri Gosain” who arrived with 6,000 of his naked warriors and 40 cannon.

There’s also a reference to Anupgiri’s services – a force of “10,000 gosain [generic term for ascetic] on horse and foot, as well as five cannon, numerous bullock carts full of supplies, tents and 12 lakh rupees [almost £16m in 2019] in money”.

A shadowy figure, Anupgiri has been described as possibly the most successful “military entrepreneur” – or mercenary – of the late 18th Century. It is an appropriate appellation: nearly all private armies hired by kings were mercenaries in those days. “A native speaking of Anupgiri said he was like a man who in crossing a river kept a foot in two boats, ready to abandon the one that was sinking,” noted Thomas Brooke, a judge in the city of Banaras (now called Varanasi).

Not surprisingly, the charismatic warrior ascetic was omnipresent. “Anupgiri was ubiquitous because he was the kind of person everyone needed. He was reviled because he was the kind of person everyone hated needing. He was the inside operator people turned to when they wanted troops, an ear to the ground, a deft negotiator, or a dirty job done quietly,” writes Mr Pinch.

Anupgiri fought his battles on all sides. In the battle of Panipat in 1761, he fought on the side of the Mughal emperor and the Afghans against the Marathas. Three years later he was present with the Mughal forces against the British in the Battle of Buxar. Anupgiri also played a key role in the rise of Najaf Khan, the Persian adventurer, in Delhi.

Later, he turned his back on the Marathas and joined forces with the British. At the end of his life in 1803, he enabled the defeat of the Marathas at the hands of the British, and helped in the British capture of Delhi, an event which catapulted the East India Company into the role of paramount power in southern Asia – and the world, according to Mr Pinch.

“The more one examines the succession of events that marked the Mughal and Maratha decline in the late 18th Century and the concomitant rise of British power, the more one sees the outline of Anupgiri Gosain in the background,” said Mr Pinch.

Born in 1734 in Bundelkhand, a strategically important province in northern India, Anupgiri – and his elder brother – were given away to a warlord by his impoverished widowed mother, after his father’s death. There are stories – possibly apocryphal – that he spent his childhood playing with clay soldiers.

Oral traditions suggest that men like Anupgiri were given permission to arm themselves in the 16th Century to fend off attacks by Muslims. But, as Mr Pinch found, Anupgiri served Muslim employers including Mughal emperor Shah Alam and even fought on the side of Afghan king Ahmed Shah Abdali at Panipat in 1761 against the Marathas. Poems celebrating his life talk about Muslim soldiers in his entourage.

“Anupgiri’s genius lay in his ability to parlay his indispensability into power. He was not high born and he knew how and when to fight – and when to run,” said Mr Pinch. “He knew how to convince opponents and allies alike that he had nothing to lose.” A world where armed ascetics could operate with a wide licence was a world in which they were “held or feared to be what they claimed to be: humans who had conquered death”.

In Mr Dalrymple’s dramatic telling of the decisive Battle of Buxar which confirmed British power over Bengal and Bihar, Anupgiri, badly wounded in the thigh, persuades Shuja-ud-Daula, the governor of Avadh, to escape the battlefield. “This is not the moment for an unprofitable death,” he says. “We will easily win and take revenge another day.” They retreat to a bridge of boats across a river, which Anupgiri orders to be destroyed behind him. And the warrior ascetic survives to fight another day.

Source : BBC