They lived in fairy-tale palaces, amassed untold fortunes in diamonds and precious stones, maintained fleets of Rolls-Royces, and travelled in specially appointed train carriages, arriving in the capital Delhi to the sound of thunderous gun salutes. They had the power of life and death over their subjects, and thousands of minions attended to their every need.

On the eve of Indian independence in 1947, India’s 562 princes occupied nearly half its landmass and ruled over a third of its population. As Britain’s most loyal allies, they were virtually untouchable – only those who committed the most heinous of crimes were censured, or, in the rarest of cases, removed. In the endgame of empire, however, they were the biggest losers, and three-quarters of a century later, all but the richest, and the most politically active, live ordinary and mundane lives.

Looking closely at the tumultuous events leading up to independence and its aftermath, as I did while researching my new book,it is clear that the princes, while fatally undermined by division and delusion, were let down by the power they trusted the most.

The rulers’ best chance of being able to preserve their kingdoms, and co-exist with an independent and democratic India, was to become more democratic themselves. However, British officials pressed tepidly, if at all, for such reforms, leaving the princes with a false sense of security.

When Lord Louis Mountbatten became the last Viceroy, the princes thought their saviour had arrived. Surely, an aristocrat like him would not throw them to the nationalist wolves? However, Mountbatten had only limited understanding of the subcontinent and left the problem of what to do about the princely states too late. He also sent out contradictory messages, insisting on the one hand that Britain would never ‘tear up’ its treaties with the states or compel them to join India or Pakistan, while at the same time going behind the back of India Office officials in London and doing everything he could to bring the princes to heel.

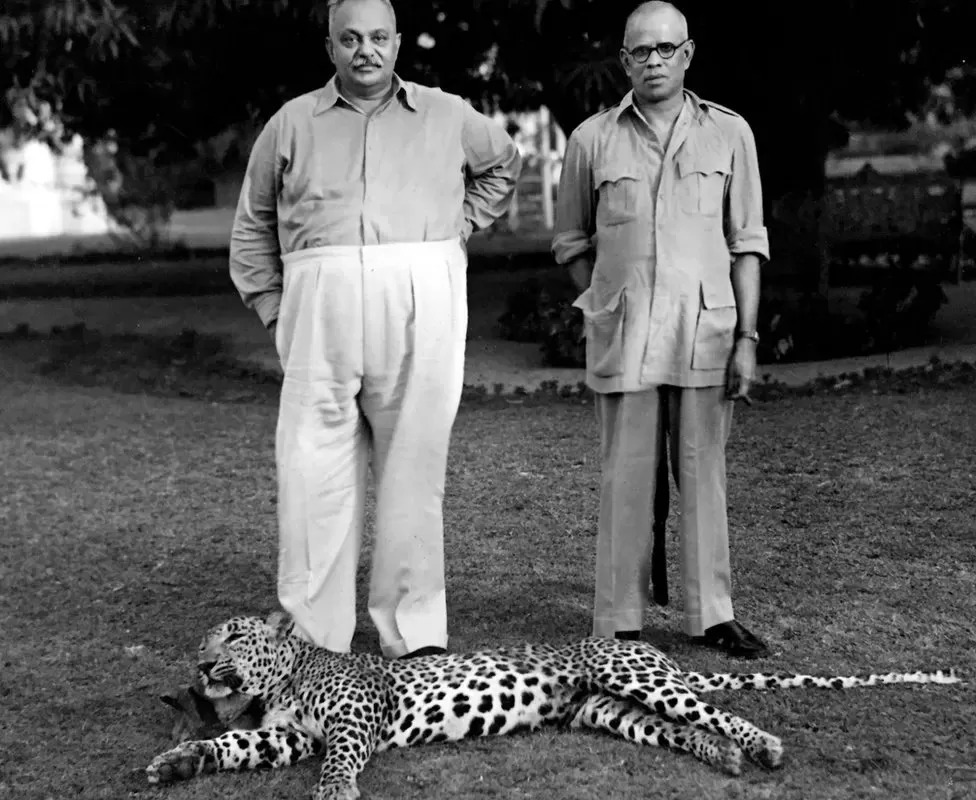

The nationalists were never big fans of the princes. In particular, Jawaharlal Nehru, who would become independent India’s first prime minister, could not stomach the existence of what he described as “sinks of reaction and incompetence and unrestrained autocratic power, sometimes exercised by vicious and degraded individuals”.

Vallabhbhai Patel, the Congress party’s leader, and the man who, as states minister, would ultimately deal with the princes, was less visceral in his reactions, but adamant that if India was to be a territorially and politically viable nation, the princely states had to be part of it. Any deviation from this goal would risk plunging “a dagger into the very heart of India”.

In theory, the princes could choose between acceding to India or Pakistan or declaring their independence once the treaties that had bound them to the British Crown lapsed on the transfer of power.

But, faced with the combined juggernaut of Mountbatten, Patel, and his deputy, the bureaucrat and master-tactician VP Menon, they found the space shrinking around them. Accede to India, they were told, and you will have control over all but three subjects: defence, foreign affairs and communications. Your internal affairs will be untouched. Refuse and risk being overthrown by your subjects without anyone coming to your aid.

With a sense of foreboding and helplessness, most ended up signing accession treaties. The few that resisted, notably Junagadh, Kashmir and Hyderabad would eventually be annexed at gunpoint, a so-called ‘police action” in Hyderabad costing 25,000 lives.

Soon enough, the promises made to the princes while signing them up were broken. Smaller states were forced to merge with existing provinces such as Orissa or into newly established unions of states such as Rajasthan. Even the larger, better governed states such as Gwalior, Mysore, Jodhpur and Jaipur, that Patel and Menon had promised would remain autonomous units, were absorbed into larger entities until the map of India looked much like it does today.

There is no doubt that integration was a lucrative exercise – for the winners. India gained roughly the same territory and population it had lost because of Partition and the creation of Pakistan, as well as cash and investments amounting to almost one billion rupees (84 billion rupees or £80bn today). In return, half of the former rulers were given tax-free privy purses that ranged in value from the £20,000 per year paid to the munificent Maharaja of Mysore to about £40 for the humble Talukdar of Katodia who worked as a clerk and travelled everywhere on a bicycle to save money.

This arrangement would last for just two decades. Men and women from royal families entered politics, some standing for Congress, now headed by Nehru’s daughter Indira, but most for opposition parties. Like her father, Indira abhorred the princes – and their success in dethroning Congress candidates was eating into her parliamentary majority. Believing that such a move would play well in her populist agenda, she tried to get a compliant president to derecognise the princes, only to be stymied by the Supreme Court, which ruled that it was beyond the president’s powers to issue such an order.

Undeterred and flush with a two-thirds parliamentary majority after the 1971 elections, Gandhi successfully introduced a bill into the Lok Sabha to amend the constitution and strip the princes of their titles, privileges and privy purses. As far as she was concerned, the time had come to end “a system that has no relevance in our society”.

Few Indians mourned the passing of the princely order and the cries of betrayal emanating from the former durbar halls ring hollow in today’s world. Unlike Britain, monarchy has no place in India’s democracy. Yet, the means to this end was often twisted. When the cards were dealt, the princes were given an unfair hand.

Source : BBC