The sensational murder of India’s best known crime reporter in June 2011 and the subsequent arrest of a female crime journalist on allegations of being involved in the murder had stunned the country.

Jyotirmoy Dey, popularly known as J Dey, was shot dead in Mumbai by men on motorcycles on orders from one of India’s most notorious gangsters, Chhota Rajan – he was convicted in 2018 and is serving a life sentence for the killing.

But somehow, Jigna Vora, a newspaper journalist, got caught up in the storm and was charged – falsely – for involvement in the murder.

She spent over nine months in Byculla jail before being released on bail. A single parent to a 10-year-old boy, Ms Vora was acquitted in 2018 since the police failed to produce any evidence against her.

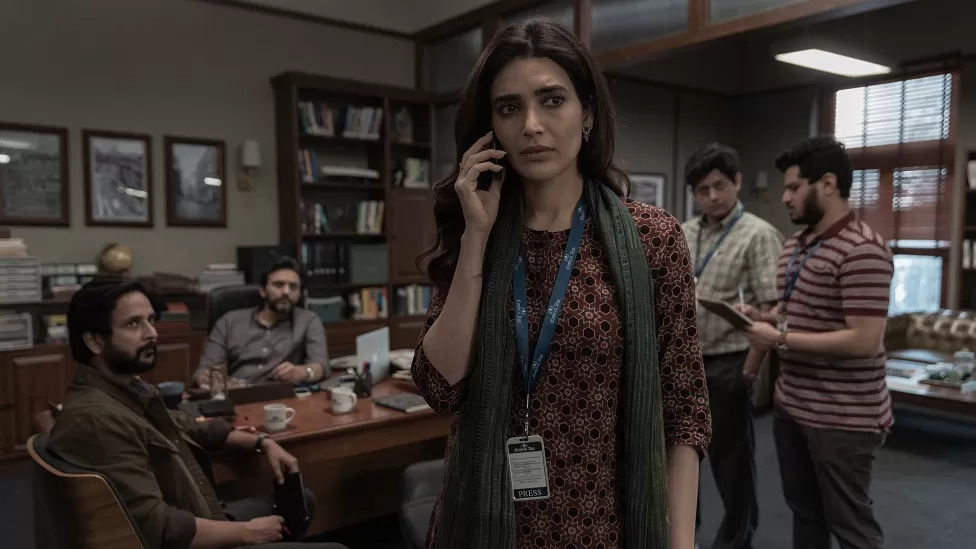

This story of a journalist’s murder – and of another’s wrongful confinement – is the subject of Scoop, a new webseries on Netflix that is wowing critics and viewers alike.

Based on Ms Vora’s 2019 memoir – Behind The Bars In Byculla: My Days in Prison – Scoop is a gripping tale of a real-life crime, Mumbai’s mafia and the role of the police and the press. Many of the real-life incidents have been replicated, but Ms Vora says “the series makers have exercised cinematic leverage”.

As Ms Vora’s screen avatar Jagruti Pathak, who lives by chasing scoops that would get her a byline on the front page, ends up in a prison cell with those she once reported on, she also begins to reflect on her life and priorities.

Ms Vora told the BBC that she’s pleased with the way the series has turned out but watching it was difficult.

“It was like revisiting the whole trauma. It was difficult to see on screen what I went through, the humiliation and character assassination I faced. But I’m happy that the series got made because people needed to see the truth that I was not guilty.

A few months after J Dey’s murder, rumours started swirling around that a female crime reporter was involved in the murder. Some of it was reported in the media, attributed to police sources.

“We were also wondering who it could be? It didn’t even cross my mind that it could be me,” she told me.

In October-end when one newspaper carried a report naming her, she says her first reaction was of shock. She then knew that her arrest was imminent – and she was arrested on 25 November.

“It was a very tough period for me, I was scared, I even thought of committing suicide, but my family inspired me to fight. They told me that if I killed myself, then people would think that I was guilty. If I wanted to clear my name, I had to fight.”

J Dey’s murder, Ms Vora says, changed her life forever. The police said she was involved with the underworld and had helped the murderers by providing them information about J Dey. She was charged under the draconian Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act (Mcoca) – a law that carries the death penalty in serious cases.

Some in the Mumbai press went after her, with many of her former colleagues taking a vicarious pleasure in her downfall. She was dubbed a murderer, a gangster’s moll. They carried unverified stories, often attributed to “sources in the police”, and criticised her for being “too ambitious”.

“I think there’s nothing wrong with being ambitious,” she tells me. “But in my case it was used to portray me as a villain.”

What hurt most, Ms Vohra says, was “when female colleagues and editors made disparaging remarks about me, saying that I was sleeping around with people to get stories, but I had no-one to tell my side of the story to”.

The series captures the media circus as reporters hound her family, including her son. The child looks bewildered and terrified as TV cameras are thrust in his face, asking him about the alleged crimes of his mother.

Prison was “a very difficult phase of life, I think it would have been for anyone in my position”, Ms Vora says. But the prison inmates, she adds, were very helpful and tried to cheer her up.

“The prison officials also treated me well, they’d counsel me telling me to take each day as it comes and that everything will be alright.”

Ms Vora, who was cleared of all charges by the trial court and then the high court, says she has “no idea who fixed me”.

“The only thing I know is that it happened – and I accept it as my karma. Now even if I do find out who fixed me, would I be able to change anything?” she asks.

While in jail, she says, she did a lot of soul searching and after being released on bail, she “started the process of healing myself”.

“I started meditating and once out, I visited lots of temples and all that helped me gain my inner strength. I was always a believer, and now my faith in God increased.”

Since it dropped on Netflix in early June, Scoop remains among the most popular shows in India – weeks after its release, it remains at number two in the list of top 10. It has also wowed critics who have described it as “a gripping tale of the fourth estate” and “a must watch for all journalists”.

Filmmaker Hansal Mehta who directed Scoop says he had followed Ms Vora’s case in 2011.

“But like all headlines, her story was replaced by some other headline. While it got confined to inside pages, she and her family bore the trauma of being labelled without judicial process,” he told The Times of India.

In 2020, when Ms Vora’s book was shared with him, he says he saw “the potential to engage with the audiences on a story that is both a cautionary tale and an important chronicle of our times”.

Ms Vora says when she heard that Mr Mehta was going to be the director, “I knew that he would be able to do justice to my story”. But, she says, she didn’t expect this kind of response.

“People are sending me messages of love and respect on social media, they’re telling me that this series has helped them see the truth, many are saying that I’m very strong – but what choice did I have?” she asks.

A tenacious reporter, Ms Vora had carved out a name for herself in crime journalism in just a few years, but after her stint in jail, she never returned to journalism. Today, she makes a living as a healer, working as an astrologer and a life coach.

The media trial that she faced more than a decade back – and the ones that take place every night in television studios where reputations are destroyed based on speculation and unsubstantiated allegations – make her uncomfortable.

Her story, she says, should serve as a lesson for the press to be careful because their reporting can destroy lives.

“The press is called the fourth estate – they are very powerful, they can make or break a person. I hope they understand the seriousness of the job that they do and mend their ways.

Source : BBC