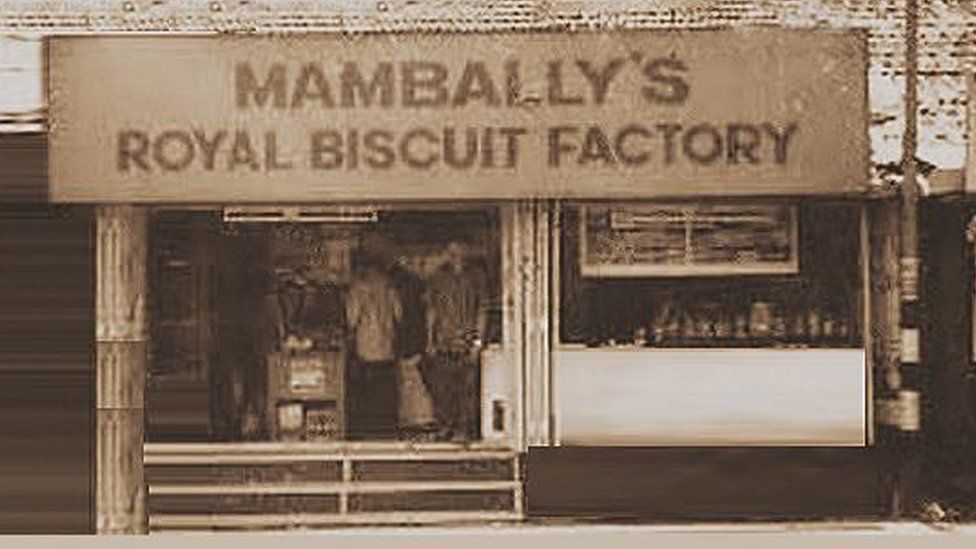

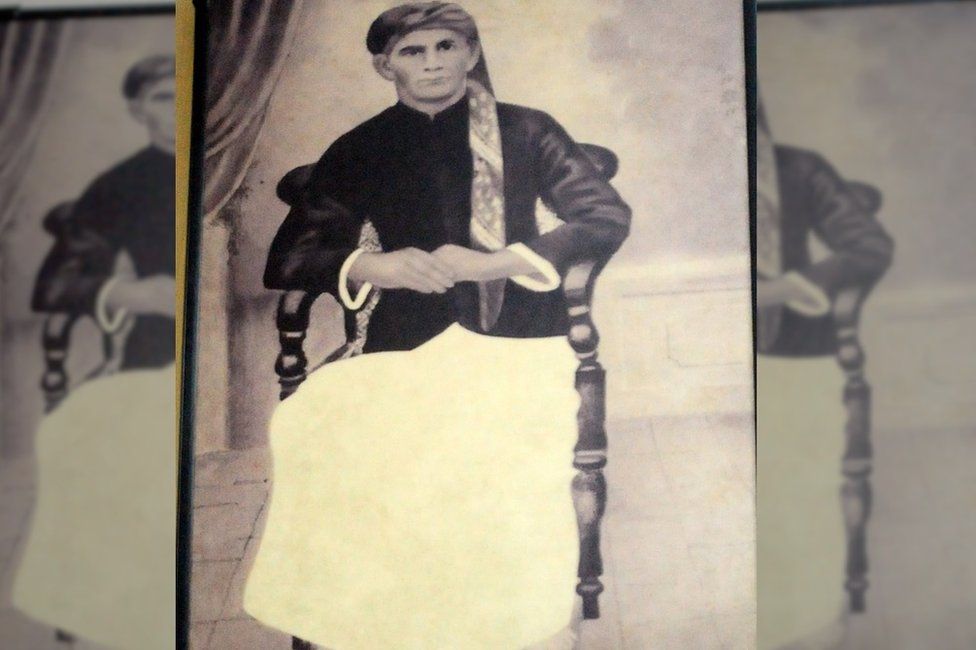

In November 1883, a merchant named Murdock Brown went to the Royal Biscuit Factory in what is now the southern Indian state of Kerala and asked its owner Mambally Bapu if he would bake him a cake for Christmas.

The Scot, who ran a massive cinnamon plantation in the Malabar region of the coastal state (then part of a princely state in British-ruled India), had brought a sample cake back from Britain. He explained to Mr Bapu how it was made.

Mr Bapu knew how to bake bread and biscuits – a skill he learnt at a biscuit factory in Burma (present-day Myanmar) – but he had never made a cake. But he decided to give it a try with Mr Brown’s inputs.

The experiment came with some improvisations.

Mr Bapu mixed the cake batter with a local brew made of cashew apple instead of the brandy Mr Brown had suggested getting from the nearby French colony of Mahe.

The result was a unique plum cake made entirely from local ingredients.

When Mr Brown tried it, he was so happy with the results that he ordered a dozen more.

“And that is how the first Christmas cake was made in India,” says Prakash Mambally, the grandson of Mr Bapu’s nephew.

While there are no official documents to back this story, Mambally Bapu and the bakery he started – which is still going strong in Tellichery (now Thalassery)- are now part of India’s Christmas lore.

Four generations on, Bapu’s descendants take pride in the legacy.

“Bapu popularised British tastes among Indians,” says Mr Mambally. “He even exported cakes and sweets to soldiers during World War I.”

Later, the Mambally family opened several outlets under different names which became a favourite destination for cake lovers.

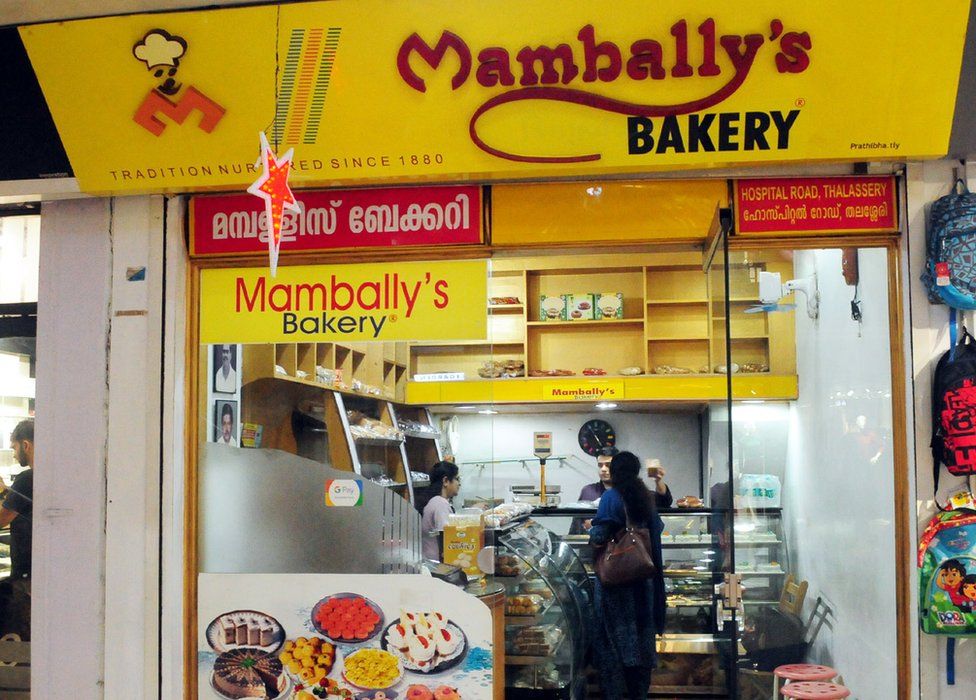

The family’s original bakery in Thalassery is now run by Mr Mambally.

His grandfather Gopal Mambally had inherited the bakery as his matrilineal inheritance, as was the tradition in Kerala at the time. Gopal Mambally had 11 children, all of whom joined the family business.

The small outlet in Thalassery, where it all began, has now been relocated to a different neighbourhood, Mr Mambally says, to make it “more visible and accessible to all”.

“But we strictly follow the traditional methods of making the cake to maintain its quality,” Mr Mambally, who is now in his sixties, told the BBC.

Over the years, the family has also added new flavours to the cake. “We now make more than two dozen varieties according to the needs of our customers,” Mr Mambally says.

His wife Lizy Prakash says that a majority of their orders come from other Indian cities like Mumbai, Bangalore, Chennai and Kolkata.

“We send them our choicest flavours by courier,” she adds.

It is not surprising that Kerala has emerged as a major centre for Christmas cakes – Christians make up 18% of the state’s 33 million people. The state is dotted with small bakeries and cafes known for their desserts.

In January 2020, the state’s bakers’ association set a Guinness world record for the longest cake in the world with a 5.3 km (3.2 miles) long cake, beating China’s record of 3.2 km.

After two years of subdued celebrations because of the Covid pandemic, the state is gearing up for a vibrant Christmas.

At the Mambally bakery, preparations for the cake started in November as the bakeries began soaking their ingredients in wine.

By the third week of December, the cakes were ready.

“Youngsters mostly prefer fresh cream cakes that have a short shelf life but this [Christmas cake] is a fast-moving item seasonally,” Ms Mambally tells the BBC.

Mr Mambally says that brisk sales at the outlet start the weekend before Christmas and go on till the New Year.

Source : BBCNews